It’s no secret that general aviation’s accident rate is significantly worse than the airlines and corporate flight departments. According to NTSB studies over the first 10 years of this century, you’re 12 times more likely to have an accident when flying your own or a rented GA aircraft.

While many of us can find creative and irrelevant excuses for this sorry state of affairs, there is absolutely no justification. The problem exists almost entirely between our ears.

Before you get started with the usual explanations, let’s stipulate that corporate and airline flight departments have some strong advantages. They use more capable equipment, often better maintained, with redundant systems that are flown by well-trained professional flight crews of two or more.

It Takes Two

But if the answer to safe flying was to permit only jets crewed by two ATPs to ply the skies, then how do you explain the fact that general aviation flight training is twice as safe as the personal flying segment of the industry?

Flight training encompasses a vast range of capabilities and missions—both in terms of the aircraft flown and the pilots who fly them. CFIs oversee everything from instrument refreshers to keeping the right side up with a newbie at the controls on an introductory flight. Those CFIs also often face what appears to be a single-minded determination by the occupant of the other seat to kill everyone on board. But their accident rate is significantly lower than ours, according to the NTSB.

No, the problem—and the solution—is sitting right there in the left seat of your airplane. We pilots like to think of ourselves as rugged individuals, which can lead to vastly different approaches to risk management. It’s time to trade in some of that individuality for conformity and rigid adherence to the safety rules.

Airlines, charters, corporate flight departments and the better flight schools all have a more disciplined approach to flying. They follow specific profiles and set strict operational limits governing every facet of flight. When you have clearly defined rules for go/no go decisions, there’s no ego involved in cancelling a flight. You’re just following the rules.

As private pilots we can do the same, dramatically reducing the accident and fatality rate in personal flying.

Structure and Discipline

That means adopting a highly disciplined, standardized approach to your flying. You set clear and unshakable decision points for every phase of operations. Those decisions points and the decisions themselves are personally tailored to your specific experience level and aircraft capability. Then you obey those limits without exception every time.

Over years of trial and error, scaring myself far more often than I’d like to remember (and more than my wife will let me forget) and reading every training article I could find, I developed a fairly straightforward approach to my flying.

They’re simple rules: 1) Follow standard operating procedures and never deviate. Never. 2) Manage risks proactively. Always have a Plan B….and a Plan C. 3) Never stop training and learning.

I have only cancelled a few flights in that time over safety concerns, and I fly more comfortably and confidently—an attitude that’s apparent to my passengers.

What’s particularly ironic about the discipline I adopt in flying is that I am otherwise undisciplined in my personal life. I never eat right, avoid household chores like the plague and am always 1,000 miles late for my automobile’s 5000-mile oil change.

But those things won’t kill you. (Well, maybe the eating part will, but that’s for another article…) However, when I fly with family, friends and associates, I make absolutely certain they get the safest ride going.

BYO SOP

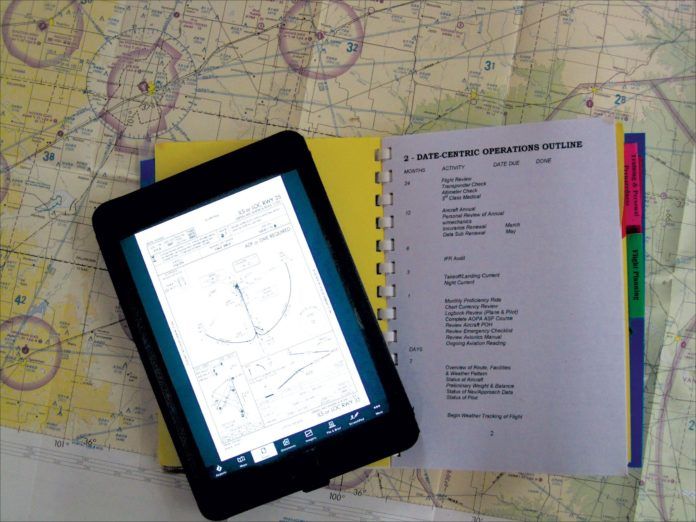

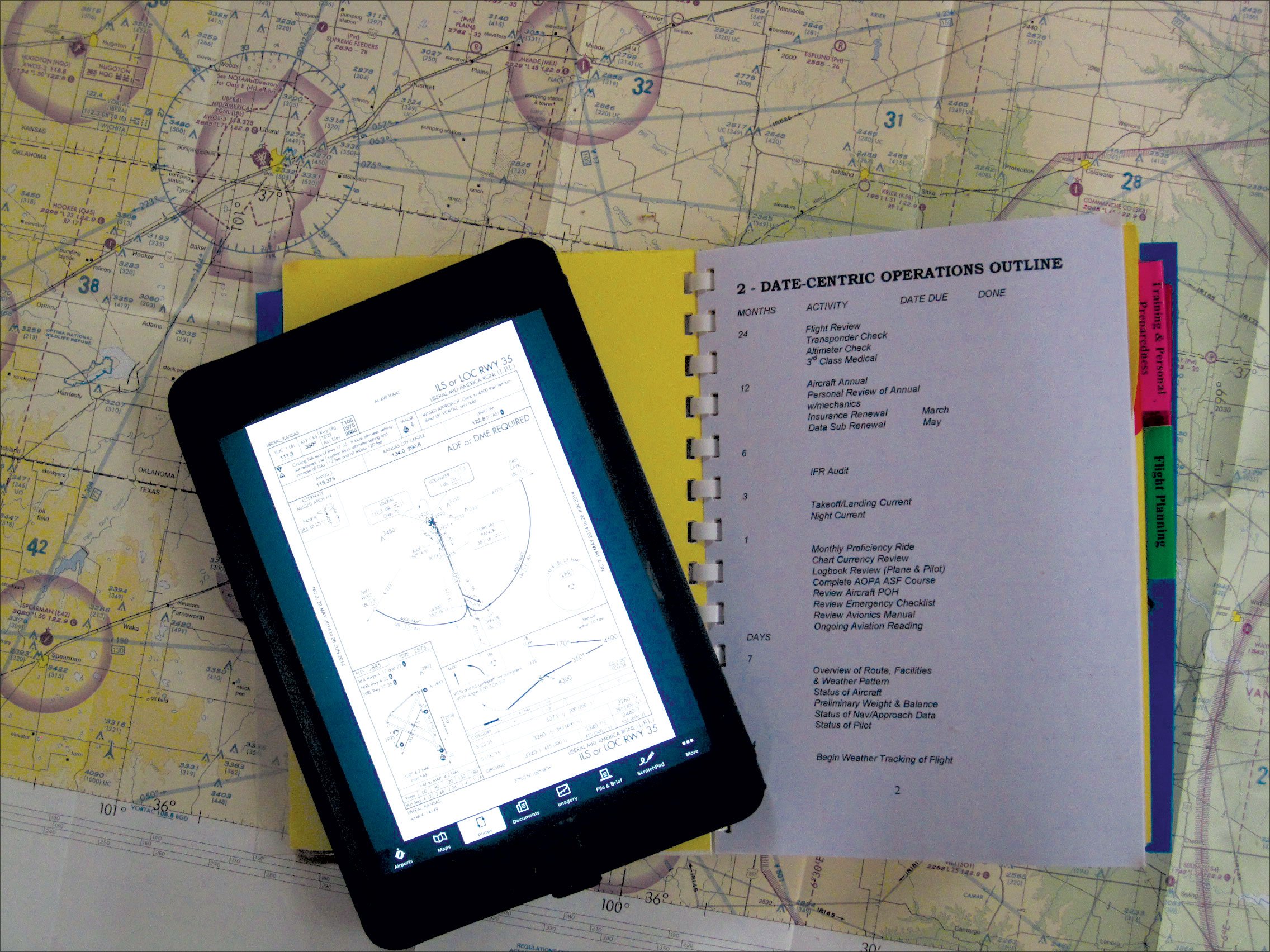

Five years ago, after reading an article crediting airline operations manuals with helping pilots manage risks, I developed my own 11-page “Personal Operations Manual.” I shamelessly copied all the suggestions, adapting as required for my personal circumstances.

I printed it, complete with a cheesy picture of me in an imitation Top Gun flight jacket draping my arm over a taildragger I once owned. It’s bound and I keep it at hand for ready consultation.

It’s divided into seven sections, starting with Personal Objectives, where I promise to fly consistently by using checklists and sticking to my personal minimums.

The next tab lists specific dates governing my operation. I established firm intervals for currency, flight reviews and critical aircraft maintenance. I included regular intervals for reviewing the POH and avionics manuals as well as the emergency procedures. When was the last time you reviewed your POH? If you don’t recall, perhaps it’s time.

Next I set out my maintenance standards, listing who will manage airframe, engine and avionics maintenance, and even how often I will conduct oil changes, washes and waxing.

The next section lays out my personal training standards, which include monthly refreshers with a CFI and establishes duty times and mandatory rest periods when I’m on the road. This is a critical element of the PAVE checklist. More on that in a moment.

The flight planning tab lays out my operational minimums, including a requirement that I compute the field length when I’m flying my turbocharged 182 out of any strip with less than 3000 paved feet of runway, a density altitude of more than 1,500 feet, or an OAT higher than 85 degrees.

This is also where I set minimum fuel requirements—one hour reserve for VFR, and 1:45 for IFR—and required forecast weather minimums before I tackle an approach. I started with a 1000 foot minimum. As my comfort and experience grew, it’s now a 500 foot minimum forecast ceiling for straight-in approaches and 800 feet for circling approaches to an unfamiliar field.

That doesn’t mean I won’t attempt an ILS approach to a well-lit runway at minimums. It just means I have a Plan B that includes approaches at airports forecast to meet my minimum requirements less than 50 miles away.

The Operations section builds on the aircraft POH to add requirements to stop the aircraft when reading the a checklist on the ground. It runs through takeoff, cruise, approach and landing, including the shutdown procedure to leave the tail beacon on to serve as a warning if I forget to turn off the master.

Avoid the Top Six

My expectation is that following the operating manual will save me from the top six causes of the fatal accidents logged by the NTSB in personal flying between 2007 and 2009.

Loss of control in flight accounted for more than half those fatalities. Regular practice with an instructor and knowing the airplane and its systems make a huge dent in the potential for getting too far behind the aircraft. Of course, maintaining instrument proficiency, not just legal currency, is probably the best countermeasure.

Many fatalities result from simply flying into the ground—controlled flight into terrain. Adhering to strict minimums, assessing proper mental and physical wellbeing and adequate rest while knowing the equipment addresses this risk.

System component and powerplant failures accounted for 13 percent of fatal accidents. While some of these are just bad luck, I’d argue that maintaining your aircraft well, not launching if you have any doubt about the health of its systems and regularly practicing emergency landings and partial panel flying would nearly eliminate this as a meaningful statistic.

All this leads us to my second “must have” ingredient for flying like the pros—managing risks wisely.

PAVE

You do use a PAVE checklist, don’t you?

You know, assess the Pilot’s physical condition (Are you tired or sick or under huge stress?), the condition of your Aircraft and its systems, the enVironment (weather conditions) and External pressures that might lull you into doing something stupid.

A pilot’s burning desire to complete a particular flight due to outside stresses and influences no doubt contributes significantly to the top three accident causes, as well as unintended flight into IMC and running out of fuel, both of which are in those top six.

I adopted a firm policy that if two or more elements of the PAVE checklist are present, I simply don’t fly. Sure, I’ll probably take a trip in benign weather if I’m getting over a cold. And if the plane and I are both in tiptop shape I just won’t worry about launching into weather that is at or slightly above the personal minimums in my SOP. But if two or more factors are present, party’s over; I don’t fly.

We pilots are control freaks who don’t like to admit defeat. But avoiding potential embarrassment by refusing to admit that some situations are simply beyond our capabilities is not a way to start a trip and often leads to bad consequences.

If I absolutely, positively have to be somewhere, I purchase a backup airline ticket. I find that without that stress of having to get there by my own flying, I’m far more relaxed and can make rational (safe) choices. It takes my ego off the line and allows me to simply evaluate the situation on its own merits without concern for the mission. Besides, with an airline ticket I’ve got someone else to blame for being late for that critical meeting.

The final ingredient of success requires us to be consistently curious and anxious to learn more—from magazines, books or just asking more experienced pilots, whom you respect, how they might tackle a particular situation that might be of concern or even just confusing to you.

Learning more means adopting a continuous training regimen that exposes you to new and ever more demanding challenges.

Learn, Don’t Fear

I used to be terrified of ice. But when I lived in Chicago I knew I’d be grounded from October to April if I didn’t learn how to deal with it within the capabilities of my simple 172.

After reading Robert Buck’s book on weather flying, I spent the winters looking for days with the perfect training environment—bases of at least 1500 feet AGL and fairly low tops. I would file IFR round-robin flights between airports that required me to climb through the clouds, see how quickly ice accumulated on the climb, then sublimate in the clear skies above, then how quickly it would again accumulate on approach.

I knew I could always descend below the bases and pick my way home outside the ice. And I quickly learned that in all but the most terrible conditions, which I fortunately never encountered, I had plenty of time to get out of icing conditions before my plane resembled a giant ice cube. The result of that practice was confidence that I could handle typical icing conditions, which avoided panic on the few occasions when I would stumble into light unforeseen icing.

On long cross countries to Florida, I would not shy away from forecasts of potential ice so long as the cloud bases were at or above the MEA along the route, and the tops were well within my aircraft’s limits. I could always cancel IFR and fly below the clouds.

I try to fly at least several times a week, in IMC whenever possible. I also schedule those monthly recurring sessions with my friendly CFI, tackling a different problem each flight.

Don’t Forget to Sim

But my secret weapon—don’t laugh here—is Microsoft Flight Simulator.

Sure, it’s fun to fly the fighter planes and pretend I’m piloting a 747 to Rome. But any simulator has practical uses far beyond the entertainment value.

Even desktop sims are a tremendous help in practicing procedures. Set the weather to minimums, then plan a trip and set the simulator to trigger one or more systems failures. Losing an engine and the attitude indicator when the weather is 300-1 is a scary prospect. But practicing scary scenarios regularly with any simulator increases the odds that should it ever happen to me for real I’ll be more focused and less panicked.

Whenever I’m going to an unfamiliar airport, especially one in mountainous or otherwise challenging terrain, I’ll fly all the approaches into that field on the flight simulator. When I actually make the trip, there are fewer environmental surprises awaiting me. Think about it: probably the worst approach experiences you’ve had are surprises from approaches you’ve never flown before. So, I fly ‘em beforehand and know what to expect.

None of this is remarkably different from how the pros organize their flying with strict operations requirements, continuous training, and adherence to minimums and procedures.

Following their regimen may not qualify you to fly a 747 to Rome, or even a commuter jet to Cedar Rapids, but it will make you a much more comfortable and safer pilot. Let the other guys play Top Gun. Boring is safer.

A member of the general media, James Warwick has been flying for 37 years. Since developing his SOP, he hasn’t scared himself, or his wife, yet he continues to extract highly reliable utility from personal flying.