With the advent of GPS approaches in the 1990’s and early 2000’s, we had many more opportunities to practice and fly non-precision approaches. Today in the U.S., with WAAS (wide area augmentation system), the reduction of VORs and the near elimination of NDBs, there are fewer and fewer available non-precision approaches. The result is more precision-like approaches which undoubtedly improves safety.

I say “precision-like” approaches because the only true precision approach available to us is the ILS with a ground-based glideslope transmitter. On the other hand, due to some technical differences that are immaterial to pilots, most RNAV (GPS) approaches with WAAS have an electronic glideslope and are referred to as APV (approaches with vertical guidance).

For practical purposes, APV approaches are flown similarly to an ILS. So, while flying an APV might be good practice for flying an ILS, none of those APV approaches—thus most GPS approaches—provide meaningful practice for non-precision approaches.

There are two flavors of APVs; APV-Baro and APV-SBAS. More acronyms. The former uses barometric input to fly the GS and are flown to an LNAV/VNAV DA(H) (decision altitude MSL, or decision height, AGL). Typically, WAAS-equipped airplanes no longer have the required equipment to fly APV-Baro approaches. APV-SBAS uses the satellite-based augmentation system (SBAS) that we call WAAS in the U.S. and are flown to LPV DA(H) to create an electronic glideslope.

We’ll focus on the LPV approaches, but first a clarification. While we use the term “LPV approach,” there is no such thing. It is an RNAV (GPS) approach flown to an LPV DA. And that is a mouthful. Similarly, there are no “LNAV” approaches. I will refer to them using the more common terms: LPV approaches and LNAV approaches.

Today

As we move forward in time with the proliferation of LPV approaches, the phaseout of non-precision approaches using ground-based navaids such as VOR, NDB, and LOC-only will result in fewer and fewer non-precision approaches. Furthermore, some WAAS navigators often provide an advisory glideslope to non-precision RNAV approaches: LNAV+V and LP+V. The “+V” refers to the advisory glideslope. An LP (localizer performance) approach is a non-precision RNAV approach that requires WAAS. Bottom line: there is almost always an electronic glideslope lurking in the shadows.

Quick Review: MDA vs. DA

While both are decision altitudes, at some point during an approach, we decide to continue the approach to the runway and land or declare a missed approach. But they are fundamentally different.

The MDA (minimum descent altitude) is associated with non-precision approaches; and the DA is for precision approaches—this time including RNAV APV approaches. There is a fundamental difference. In the Instrument Rating ACS (Airman Certification Standards), the MDA standards are +100 feet and -0 feet once at the MDA. This means it is a “hard” altitude: Thou shall not go below unless one of the 10 items in 91.175(c) is visible.

The standards for DH are not specified in tolerances but the pilot must “immediately initiate the missed approach…” This means that the regulations allow the airplane to descend below DA during the miss. For instrument students getting ready for the instrument practical or instrument pilots doing an IPC (instrument proficiency check), ask the examiner or CFII how much he or she will allow you to go below the DA when executing a missed approach. Don’t be surprised if you receive a quizzical look. For a light GA airplane, 50 feet would be a reasonable tolerance.

Selection of Alternates

Without getting into the whole discussion of alternates, there is one area that is relevant. Typically alternates are selected based on weather conditions at the ETA at the alternate. But that is not quite right. The standard alternate minimums for planning purposes is 600-2 for precision approaches and 800-2 for non-precision approaches. Any given approach might require more. This means that when we are selecting an alternate field, we are really selecting a particular approach to an expected runway. Since RNAV approaches flown to LPV minima are not technically precision approaches, all RNAV (GPS) approaches are considered non-precision; therefore, the standard non-precision minimums apply: 800-2.

That was for planning and filing purposes only. If we need to deviate to an alternate—filed or not—the landing minimums used are the ones published on the approach charts.

Instrument Practicals and IPCs

As discussed, since APV approaches are not precision approaches, Appendix 7 of the instrument rating ACS allows a GPS approach flown to LPV minima to be considered a precision approach if the HAT (height above touchdown) DH is 300 feet AGL or less.

Full Circle

We started by saying that at the introduction of GPS approaches, all were non-precision; to be more specific, they did not provide vertical guidance. We had many to choose from. Fast forward today, with the proliferation of APV approaches that do provide vertical guidance. We have many approaches with a glideslope, and now we have the opposite problem: not many non-precision approaches. Instrument flight tests and instrument proficiency checks require demonstrating flying non-precision approaches. But how can we practice them, especially with the glideslope right in front of us?

I’ll focus on southeast Florida; other areas of the country might be different.

There are only two non-precision approaches in southeast Florida; a LOC-only approach at Pompano Beach (KPMP), and a VOR approach to Boca Raton (KBCT). All the other approaches have glideslopes whether “real” or “advisory.” With the intense amount of GA activity including training, here are our options:

1. Get rid of the non-precision approach in the ACS. Not realistic at all given that there are still many non-precision approaches across the country and internationally.

2. Pretend to ignore the glideslope. While this might be practical, as a heavy-iron pilot once told me, “one peek (while under the hood) is worth 1000 scans.”

3. In some round-dial aircraft, the number two navcom might have a dedicated VOR/LOC head without GS. In this case, fly an ILS approach with #2 using only the displayed LOC. But that too is not realistic given the availability of airplanes with only a VOR/LOC head and that most of the available ILS approaches are at busy airports.

4. Fly 90 NM over the Everglades to Naples Municipal (KAPF) on the west coast of Florida and fly one of the two VOR approaches there. Besides the practicality (and cost) of flying 180 NM round trip, either of the approaches might conflict with the active runways. And avoid Friday afternoons when the jets from the northeast U.S. arrive and Sunday afternoons when they fly back.

While there are plenty of approaches in southeast Florida (62); all but two have glideslopes, making them essentially useless to the pilot looking for a non-precision approach.

Go WAASless

So where does this leave us? There is a simple solution: turn WAAS off. (When asked, few pilots know how, or care to turn off WAAS.) By turning off WAAS, all of those RNAV approaches will show up as LNAV approaches. The LPV GS disappears, as do the advisory ones (+V).

Let’s go through how to turn WAAS off in a Garmin GTN navigator. If you have something else, you’ll need to do some research.

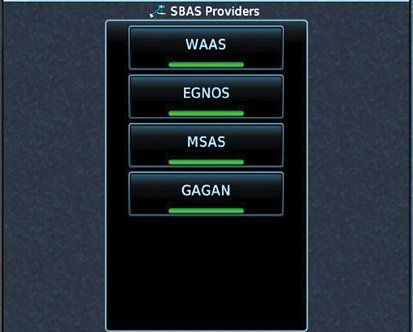

From the main (home) menu, select System. Then select GPS Status. At the bottom of that page, select SBAS and turn off the SBAS you’re using. (WAAS in U.S.; EGNOS in Europe; MSAS in Japan; GAGAN in India)

There is only one issue with this, especially after December 31, 2019. If the GPS navigator is providing WAAS LAT/LON input for ADS-B Out, ADS-B Out will be disabled. That simply means that you have to be outside ADS-B Out mandated airspace, and don’t forget to re-enable WAAS after the approaches are completed. If you have two WAAS GPSes, you might want to know which one is serving ADS-B and use the other one for non-precision approaches. Let us know how this works for you and how you turned off SBAS in your navigator.

It used to be challenging for Luca Bencini-Tibo to find precision approaches in southeast Florida. Today it’s the opposite: non-precision approaches are scarce.

you need to update this article. there is no longer a vor appch in kbct. the new appch, a gps, rwy 23, should explain in detail the 34:1 not being clear. this is more important than all garmin pictures you display. the vast majority of corporate jets have Honeywell or Collins, not this cheap garmin crap. The vast majority of pilots dont know what 34:1 not clear, OR visual segment obstacles truly means.

A very good article, Garmin Navigators are the best in GA aircrafts and others have similar logics. Discussion about how to get a non-precision approach practice now days is is perfect and relevant.

Than you