Here’s a scenario familiar to many: You’re preparing for an early flight on a crisp morning. The autumn sun’s coming up as you look forward to that smooth ride and a million miles of vis. Then, like a magical but unwelcome specter out of thin air, a coat of frost appears on the wings. Is this a “So what?” or “Argh! Now what?” situation?

It’s the latter, if you’re aware of the legalities. In the end, it’s down to prevention, mitigation, and one of three outcomes: go, delay or no-go. This chain of decisions can happen repeatedly for a variety of situations that can arise both before and after you fire up.

Icing, Maybe

You’re flying two passengers from Bowling Green, Kentucky to Rochester, Minnesota. Clear skies bless half the route, followed by a cloud deck for the remainder with tops between 9000 and 12,000 feet. Bases in the Rochester area range from 500 to 1500 feet. The terminal forecast at KRST indicates you can expect to break out around 1000 feet AGL.

Sounds benign, but are you looking at the weather system itself, not just the resulting conditions? If you’re checking “weather reports and forecasts” and calling it good with METARs and TAFs, is your “preflight action” really complete?

Do a standard briefing, and you’ll spot two red flags. First, there’s an AIRMET Zulu present in Minnesota that dips into the last 40 miles of the route: Moderate ice above 3000 feet, layered up to 12,000 feet. Second is a NOTAM: The RST VOR is out of service for the next three days. Either could potentially spike the mission.

It’s certainly legal to fly through the AIRMET. These are advisories covering large areas. But it behooves you to determine that your flight plan won’t enter “known or forecast light or moderate icing conditions” as prohibited in 91.527. Here goes. There’s a stationary front just west of the route, bringing in cloud layers and scattered showers. Freezing levels will hit between 7000 and 12,000 feet. So, at 8000 feet, you do risk picking up ice. One lone pilot report from a single-engine turbine over Iowa shows negative ice in climb from 3000 to the tops at 11,000. This isn’t all that useful since you’re flying lower and slower, but you are willing to climb as high as 12,000 feet to be on top. Your Plan B, while not at all mission-friendly, is to turn back to warmer air and land in Iowa, or even return to Bowling Green if that’s best.

91.103 Preflight Action

Each pilot in command shall, before beginning a flight, become familiar with all available information concerning that flight. This information must include –

(a) For a flight under IFR or a flight not in the vicinity of an airport, weather reports and forecasts, fuel requirements, alternatives available if the planned flight cannot be completed, and any known traffic delays of which the pilot in command has been advised by ATC;

Check the Chart

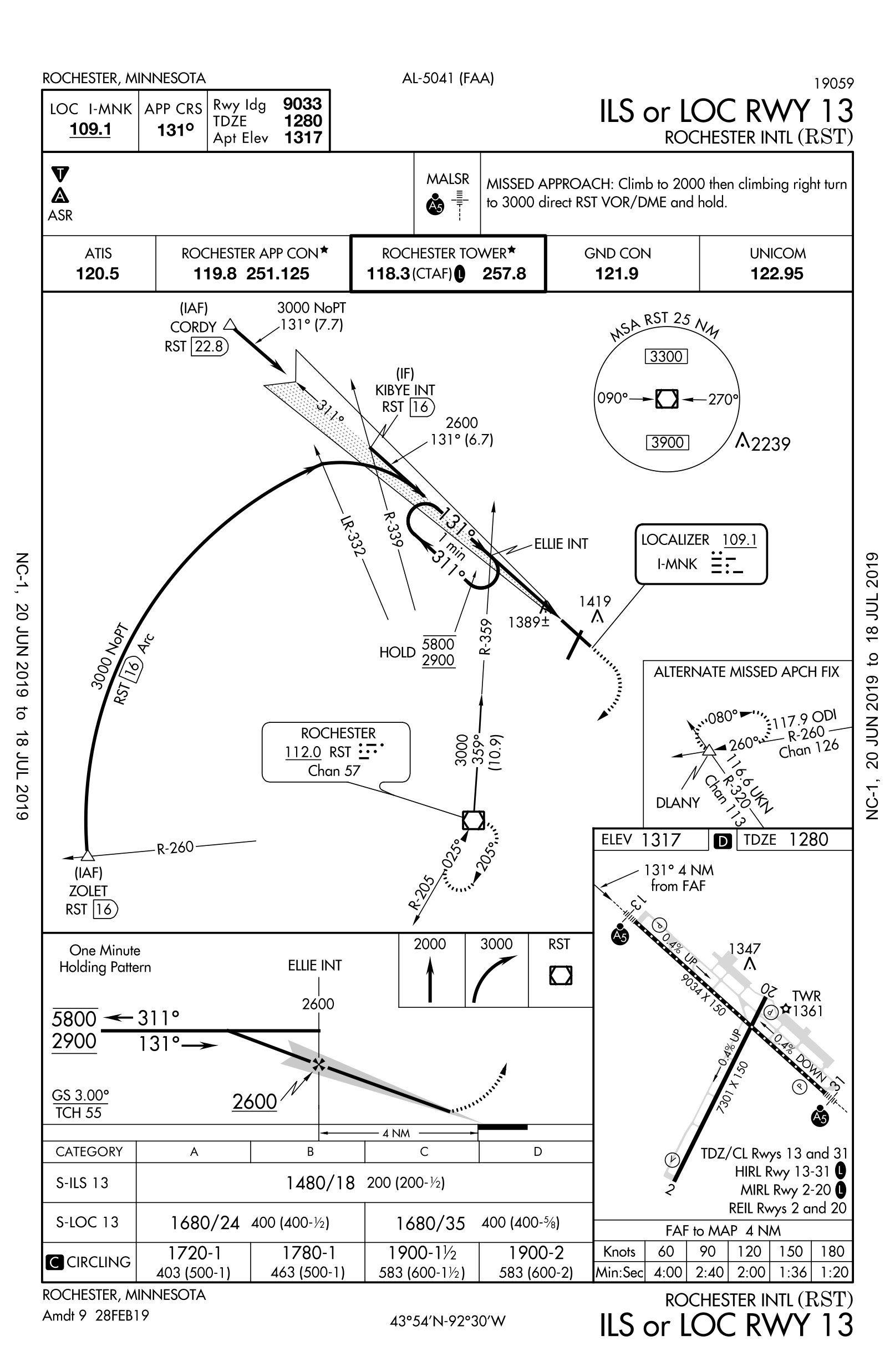

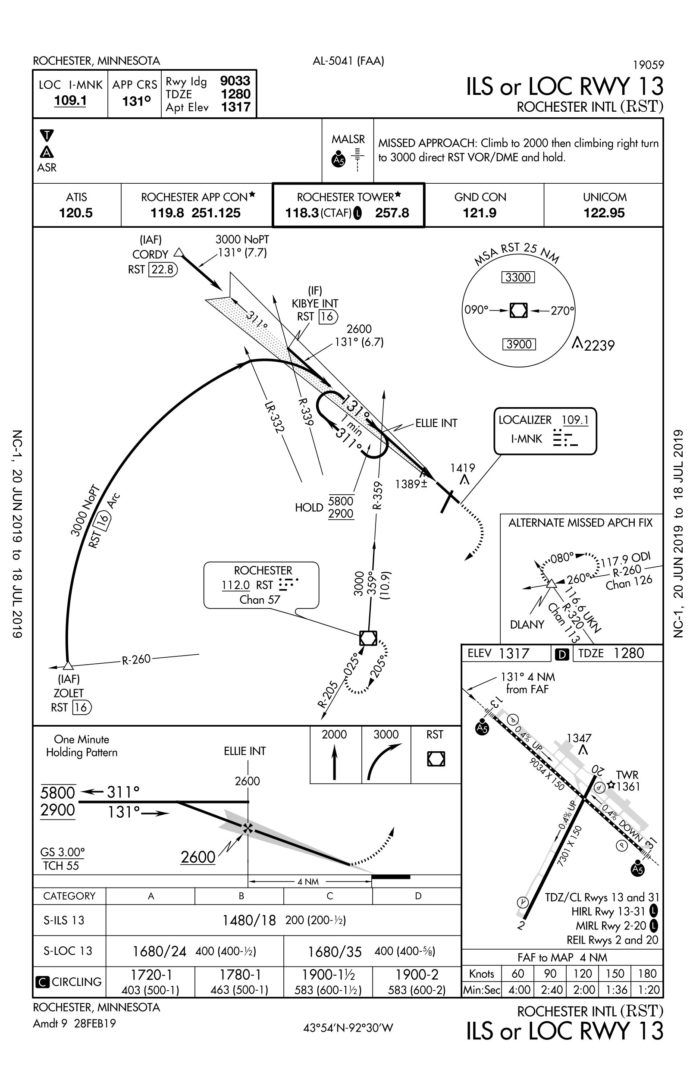

Now for flag number two. With southeasterly winds today in Minnesota, you can expect the ILS 13 for approach to KRST. For what you’re flying today—a six-pack with dual navs, sans RNAV—this could rule out the approach for you. Why? An approach includes the missed and missed holding fix. For the Rochester ILS 13, going missed at or before the 1480-foot decision altitude means you then “Climb to 2000 then climbing right turn to 3000 direct RST VOR/DME and hold.” But, RST is out of service.

Fortunately, the IAP includes an alternate missed approach fix depicted on the plan view—DLANY, a fix off the ODI and UKN VORs. By the way, if you’re checking “all available information,” you’d already know the alternate missed is NOTAMed as the procedure to use. (For more on alternate missed procedures, see Lee Smith’s excellent article, “Missing Something?” in February 2014). It sure pays to check NOTAMs, as cumbersome as they are. If you’d arrived unaware, chances are that the ATIS or someone would’ve informed you of the outage, but the legal obligation of checking per 91.103 is up to you.

Frost Happens

Fast forward an hour to the ramp, 20 minutes before takeoff. Another red flag: Frost. You thought you’d dodged that bullet by delaying exiting the hangar and getting the fuel truck there just before boarding. The latest METAR says the OAT is -1 degree C and the dew point is -2. Well, that truck had been sitting out in below-freezing temps all night. Now, the cold fuel pumped into the low-wing tanks quickly chilled them below the dew point and you see the result.

Time to get to work. De-icing procedures are always an option, although isopropyl alcohol and propylene glycol usually aren’t sitting around (perhaps they should be…). The flight slides behind schedule as you brush frost off with a hangar broom. After a good 10 minutes, there remain a few rough patches on top of the wings. Is that good enough? Recall that 91.527 does prohibit flying “an airplane that has frost, ice, or snow adhering to any propeller, windshield, stabilizing or control surface…”

Do you launch, knowing that you could triple your usual 1800-foot takeoff roll and still have plenty of runway remaining? Realistically, yes, so you’re safe—but not legal, because 91.527 takes into account that there’s no answer to the question of how frost on your wings would increase your takeoff roll, or affect your ability to out climb the obstacles on departure. Your best bet is to taxi out into the rising sun and wait. Only way to be both safe and legal. You decide that if you’re 30 minutes late, you might as well make it 45.

Mostly Legal

Fast forward another three hours at 10,000 feet. Just as you’re patting yourself on the back for flying ice free (from luck and altitude), the clearance to descend to 3000 feet brings on the light rime, just like the AIRMET predicted. You are indeed in “known icing conditions.” Are you safe? So far there’s no noticeable effects, as long as you don’t accumulate any more. Legal? Not really, but you’re nearly there. Do you report it? You don’t like the thought of getting delaying vectors, so you fess up, and an appreciative Approach also asks for bases on the ILS. You break out at 1100 feet on a mile final. Although you did land with some airframe ice, you had reason to believe it would be safe, short-lived and were prepared to divert or even fly home, which not everyone is willing to do.

Elaine Kauh is a CFII in eastern Wisconsin, where the three months of ice-free flying is well spent stocking up on propylene glycol and extra mittens.

Elaine, i teach every day in turbojet a/c. NOBODY USES NOS CHARTS, NOBODY. Why not use Jeppesen, which is the standard?