On occasion I have a flight “across the pond.” No, it’s not an ocean crossing, although it sometimes feels like it. These flights cross Lake Michigan, and require a bit more planning than flights over land.

When you fly around the Great Lakes, it’s taken for granted that if you’re in a single-engine piston aircraft, you have to carefully examine the risks and mitigations. Don’t want to cross the lake at all? Fly around it and spend that extra time to stay over land. Not good weather for a crossing? Same deal.

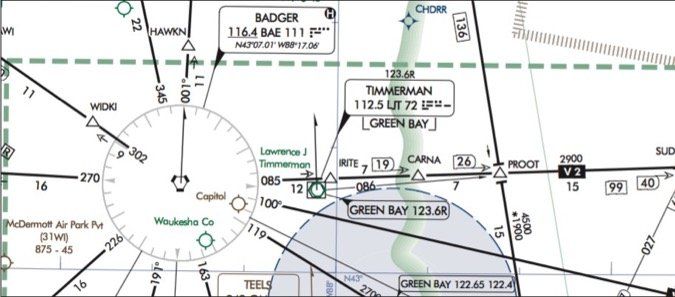

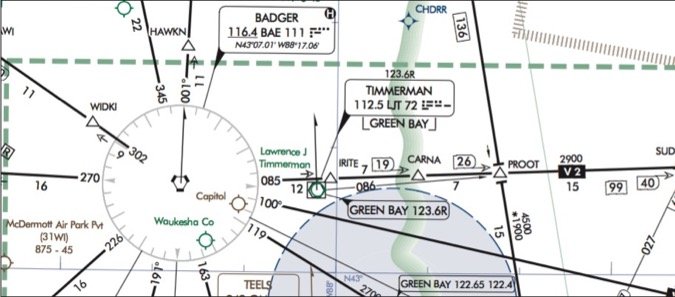

There are a couple convenient fix-to-fix routes and airways that take you over Lake Michigan while avoiding its widest segments. One I often get is BAE (Badger) V2 MKG (Muskegon).

That’s an easy flight plan. Now, there are three burning questions about that crossing to address before you top-off the fuel. First, how high do you go? Second, do you want to take any special equipment, and third, what weather conditions are you willing to accept while flying across the lake?

How High?

Common sense tells you that the altitude options will start no lower than 11,000 feet, with 13,000 and 15,000 feet even more appealing. Your POH has climb charts to help estimate the time and nautical miles to reach selected altitudes.

For example, a Cessna 206 table offers numbers for climbing from sea level up to 14,000 feet. Assuming you start at maximum weight from about 1000 feet leaving Madison, the climb to 14,000 at 82 knots would take about 28 minutes and 43 NM. Other climb tables in the POH offer different weights and speeds, but all things being equal, you can see that you’ll reach the lakeshore at the desired enroute altitude as you have 65 NM to do it. That’s the mileage from KMSN to CARNA, a fix on V2 that’s just off the lakeshore. So far so good.

The emergency chapter (Section 3 in modern handbooks) will have a gliding distance chart. In the light-piston category, you can expect most charts to give you 15 to 20 NM of glide distance in that 12,000 to 14,000 foot window, which is the case in the Cessna 206 example.

But on this route, it’s 68 NM from shore to shore, so assuming a (conservative) groundspeed of 130 knots, you’re looking at maybe a half hour over open water, with over 10 minutes out of gliding range. This should give you pause.

Part 91 operations that are not for hire aren’t required to have flotation gear per 91.205(b)(12). But everyone flying some kind of for-hire or large-aircraft operations must have appropriate equipment, so it behooves you to do the same, even if it’s just wearing good, comfortable life vests on the flight. Most owner-pilots around the lakes do just that.

Most also have portable oxygen. Perhaps you could get the flight portion that’s above 12,500 feet under 30 minutes to satisfy the oxygen requirements under 14 CFR 91.211. But you might need it anyway for flying above 14,000 feet because, well, being conscious and alert is kind of important here.

A Close Look At Weather

While reviewing this scenario, I happened to check real-time weather showing ceilings from 300 feet at Milwaukee to 500 feet at Muskegon. Unseasonably warm late-February temperatures were steady for most of the route at 10 degrees C. Freezing levels were in the range of 7000 to 9000 feet, with a moist warm front south of the route. This made it plenty ripe for moderate icing conditions in that altitude window.

Climbing and descending through a 2000-foot icing layer would be a no-go for most single-engine piston pilots. If that’s not enough, unfavorable winds often arise that are strong enough to significantly prolong the time over the lake.

If it had been a more typical month for winter conditions, the temperatures at the surface would have been well below freezing, making it cold enough at altitude to solidify the tiny droplets that make up the clouds and greatly reduce the icing threat. Also, normal winters see cloud tops in the 6000 to 7000-foot range, making it easy to get on top in smooth air with the sun warming the cockpit.

However, the main show-stopper is the time of year. Most of us, myself included, will not cross even the narrowest part of Lake Michigan (which is about 43 NM) in the winter. Water temperatures can remain below survivable levels well into the summer. Indeed, many pilots won’t fly such routes at all.

One More Thing

If you simply file direct without planning the route—a trap with tablet GPS—you can get a nice nav log with miles between each fix and current weather calculations for fuel and speed, if you’re so inclined. But then the bubble bursts if you happen to get around to tapping for the enroute chart to peek at where it takes you. Our route shows there’s a gray zigzag over the eastern segment of V2 just before reaching the MKG VOR.

What is that? As with any chart symbol you haven’t seen before or don’t recognize, you can easily find out what it represents on the chart legend or in the FAA’s Aeronautical Chart User’s Guide. (While most of the common symbols appear on the legend, a full listing is available in the guide.) This symbol tells you that there’s an “unusable” segment of the Victor airway.

What does “unusable” mean here, anyway? And another question emerges: Does this affect that nice, simple flight plan you created, or can you disregard the fact that V2 is unusable for the eastern portion of the lake crossing? If you’re navigating with RNAV direct to MKG, no issues here—just know that radio-based reception on the airway to this VOR might not be there for you. But should that happen to be your primary source of IFR navigation, you’d be faced with decisions involving other routes, or perhaps flying under VFR to get around navigation requirements.

The last time I discussed this scenario with a group of local pilots yielded lots of food for thought. The opinions were varied as to whether one would even consider flying single engine across Lake Michigan. Beyond that, there was general consensus that oxygen and flotation devices should come into play, and most wanted weather a bit better than what they’d normally fly in just to avoid the potential of unexpected conditions.

The biggest variable aside from personal minimums and equipment was the type of aircraft and its capabilities—how high can it go, how fast can it go, and does it have fully coupled RNAV? Once we figured out what we’d be willing to do, we also discovered that it pays to check the charts.

Elaine Kauh is a CFII in eastern Wisconsin. She has learned from crossing Lake Michigan that engines do make funny sounds over water, but only when you look down.